Central to this body of work is the concern: if space is idea and aspiration, whose desires does it fulfill? When the Tower of Babel was imagined, the inherent politics of architecture became a manifest metaphor. As a structure it became a symbol of incoherence; its walls emblematic of the first borders between men. In the gradual progression from empire to nation, to city to buildings, the tower continues to remind us of space and structures as sites of exclusivity.

In his very considered body works titled Absence of an Architect, Gigi Scaria compresses the visual field of his city into a series of vistas, forcing an engagement with the political and social dimension of building structures. The fact that he works in three media – painting, photography and video – allows for different levels of expressivity.

From Kothanalloor to Nai Dilli

The long journey from South Delhi to Gigi Scaria’s studio in Rohini requires a map. Not unlike Scaria’s own journey from Kothanalloor village, Kottayam district, Kerala from a life informed by the village church as a centre of activity, the row of shops that his parents owned and their house adjacent to the shops. This triangle of activity was a safe haven for the Scaria household between the village school, the church and the shops, one broken by the artist when he made the first trips to the local library. In the conservative Catholic scheme of things, any inclination on the part of a young boy to read Dostoevsky rather than weekly catechism would have posed a threat to the tenuous familial fabric, one sustained in the face of a visible and vocal left politics. But the Church offered Gigi oblique opportunities for artistic exploration. Of more enduring interest than Sunday school was the Christ figure, redolent in Catholic churches that offered the first possibility of studies in human anatomy. With clay from the paddy field and his grandma as guru, Gigi as a six year old had started to construct the agonized figure on the cross. He learnt the details of the musculature and form as defined by colonial and local priests. Further instruction came from reproduction of Renaissance painting and sculpture in the Malayalam magazine Bhasha Poshini.

Malayali Christian resistance to the presence of the left, to popular cinema as well as absorption at other levels of ethnicity made for a delicate negotiation in terms of cultural identity. Gigi’s response was to continue to scour the local library. As he determined to be an artist he enrolled at the Government College of Fine Art, Thiruvananthapuram.

In 1995, Gigi came with fellow artist Josh P. S. to Delhi. His first job was with Bhagirathi art studio in Amar Colony where he illustrated nursery text books. In his next place of work, Naiwala gali in Karol Bagh he worked on a school text book painted in gouache in the morning hours, with visits to the Lalit Kala library in the afternoon. In 1996, Gigi joined the Jamia art department for a masters degree. At the same time his readings in contemporary Malayalam literature, of OV Vijayan and Ananth confirmed the artist’s position at the site of traversal, between history and society. Encoded in his personal journey was his perception of how he was seen in Delhi - student, small budget, dark man.

Migrant I Worker

This present body of work comes on the heels of Gigi’s continuing engagement with the city as migrant/ worker. From his small flat and studio in Rohini what the artist successfully communicates is the great desire to engage with the city as experiential base, the mirror of the migrant. Delhi as a city is impermanent, its structures malleable, its roads fluid with surprise contours. It is a site under construction. In Panic City, (video, single projection), buildings loom and rise and slide out of vision. Shot from a minaret of Jama Masjid, once the heart of Shahjahan’s imperial India, this view engages the city, its poetry, its oppression, its wretched eternality, a vision where is no relief, no pause even for a single breath of gladness. From the precipice of the minaret the artist abandons the view of the biker or the pedestrian for a bird’s eye panorama. Where the intense human detail is eroded and we see instead uneven structures that careen momentarily upwards as if in a moment of syncope, pushed to the edge of an insistent vertigo.

Almost without deliberate intention, the artist as migrant stumbles upon the lost heterotopias of the past and the present. The city of Delhi was raised in historic spasms, becoming the ground of a shifting consolidation of empires, faiths, peoples, structures, aspirations.1 Gigi’s work reflects the shifting nature of the city, its historical accretions, layers of migrancy and its elusive heart. This journey of the migrant translates into metaphors of quest, seeking to negotiate a labyrinth. Like Borges’ elucidation,2 the labyrinth comes to represent our negotiations in the physical world, and the absolute limits of human knowledge. There are other cultural models of the labyrinth. Here one may choose the intensely diagrammatic Sri Yantra, which with the intersection of 48 triangles creates a map of metaphysical negotiation (as compared to the void of the journey in the wilderness, of the Christ or the Buddha). This yantra sets up routes, intersections, directions geometrically defined spaces that lead through seemingly impossible negotiations to a void/infinitude.3 Panic City abandons the intimate documentary tone of Gigi’s earlier works, A Day with Sohail and Mariyan, (single channel video projection) and The Interview, (three channel video projection) for this anxiety-inducing vision of the avid, growing city.

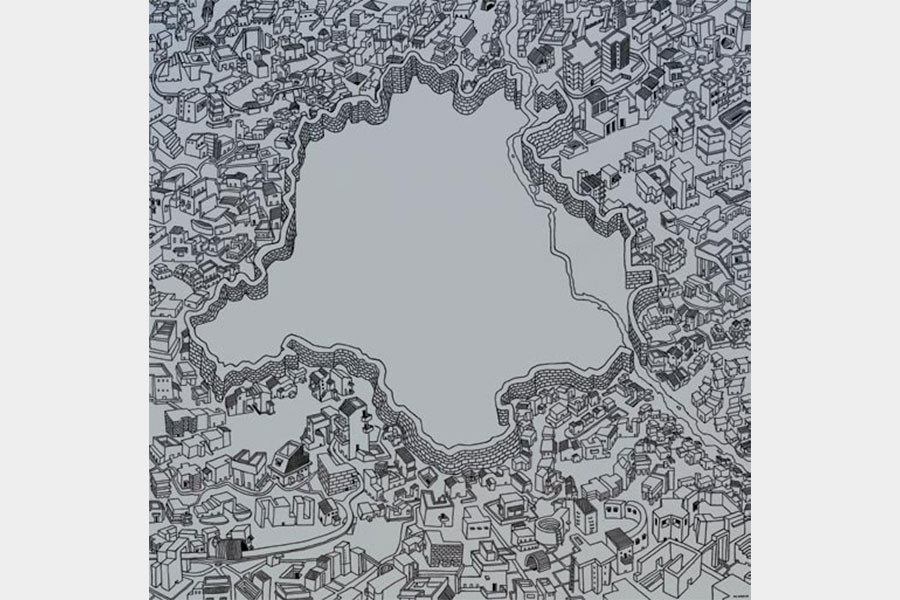

It is the same view, of physical distance, that Gigi assumes in his paintings. The series titled Options of an Alternative Master Plan are located within the chaotic politics of the present, with the current announcement of the Master Plan for Delhi for 2021. Even as the city grows, swallowing up fields, village tracks, towns, habitations, the question of location remains urgent. In Gigi’s view, the conventional volatile elements of the city – its people – have all been erased. What we see instead is that its rooted structures are rendered unstable. Hot, treeless cement facades present a new vision of the city as uninhabitable. In the painting Keep Delhi Clean the map of Delhi appears like a brick wall, which evacuates from within its borders every form of life, a travesty of the structure of the densely populous walled city of Old Delhi. In a sense this works like a mirror image of the work Opening Shortly, a grid of 49 photographs of shutters of shops, holding out the promise of a better life.

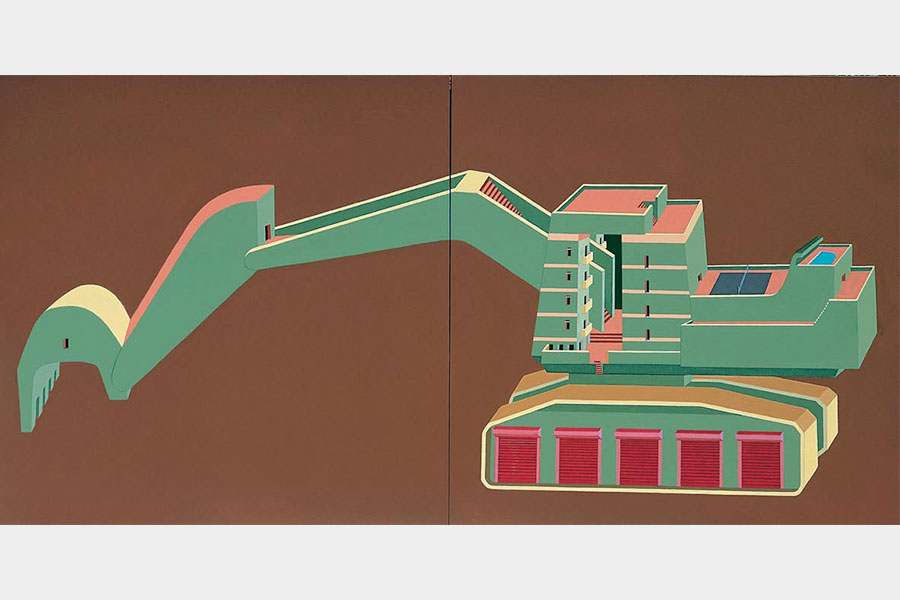

In this labyrinth the artist enters different historical sites, from the pre Mughal step well of Agrasen ki Baoli to the shuttered exteriors of new shops. His camera mimics this encapsulation of history, zooming in from single shutter detail to panoramic views of the city. The photographs on view represent the different accretions of Delhi, the uncomfortable disjuncture between monument and building, between past and present, with their implicit questions of inclusivity and ‘value’. Like Borges, Gigi Scaria is not interested in developing a language of visual poetry, but works in the mode of the anthropologist/documentary maker – fulfilling the view from the periphery. In this context the painting Delhi Mall rises like an anomaly that draws into itself histories, aesthetics, and styles, like the ultimate architectural monstrosity Painted in the vivid colours of calendar art, it mimics the collapsed vision of a hundred dreams, a lunatic heterotopia,4 one in which the DDA flat, Parliament House, a shopping mall, Jantar Mantar all come together in a terrible collusion of visions. This mad accretion challenges the idea of cultural specificity and location. Rearing like a Tower of Babel, where no one speaks the same language, it also posits the idea of a fractured aesthetics and social dissonance.

A Sociology of Structures

Gigi’s particular position is to investigate how city structures, social constructs, and the view of location is translated into social prejudice and class attitude. The video work titled Site Under Construction bears many of the marks of the artist’s characteristic style, of an apparently innocuous conversation suggestive of a narrative, one that reveals at its core, deeply ingrained prejudice. Two middle class neighbours, one a house maker, the other an architect reflect on a subject of mutual concern, housing. Even as they speak an apparently poor labourer sets out to ‘construct’ a small dwelling, in the courtyard, only to violently demolish it. The site that is deconstructed is reminiscent as much of the recent demolitions along Delhi’s streets as of the bull dozing of slum clusters, and the displacement of squatters within Delhi. Equally this work (like Gigi’s earlier The Interview) demonstrates the stereotype or the ‘reading’ of the migrant as poor, dark and homeless, an unwelcome squatter in the city’s public spaces. One may extend this image/narrative to a broader history of social exclusion, of seeking to expose the view and the attitude of the priviledged classes. Site under Construction bears an active relationship with the photographic work of the same name. As the eye gradually moves from left to right in this panoramic view of mean city huts the human presence dwindles and the cluster of huts appear gradually desolate and abandoned.

Gigi Scaria’s work demands considered attention for its investigation of the issue of migrancy and displacement. One realizes with consternation that the artist/migrant like the labourer/migrant has only moved from one part of the country to the other, yet the issues of non-belonging echo the spirit of diaspora. But while the diaspora artist has the luxury of the evocation of the homeland, and devises a language of loss, the migrant within the homeland lacks even this singular pleasure. Scaria is of course not alone; the use of the context of desh/pardesh is repeated in multiple ancient medieval and modern contexts. In the volume Poems of Love and War.5 Ramanujam highlights the difference between Akkam and Puram in ancient Tamil poetry between the private and the public, between the hearth and the public field, each of which invites a different language of expression. In numerous north Indian dialects, the schism between the personal and the familiar and the external and the ‘foreign’ is the binary of desh/pardesh frequently used by the Bhakti poet Kabir on different registers of metaphor. In this way the journey from Kothanalloor to Nai Dilli is problematized not only in terms of contemporary urbanism and its relentless spread but at the metaphysical level of belonging and community.

Gayatri Sinha is an independent critic and curator, she lives and works in Delhi.

Footnotes I References

- Delhi as imperial city has been the site for Indraprastha (1450 BC) Lal Kot or Qila Rai Pithora, (1060 AD) initiated by Rajput Tomaras in the mid 8th century and extended by the Chauhan kings; Siri, (1304 AD) built by Alauddin Khilji; Tughlaqabad (1321-23 AD) built by Ghiyasuddin Tughlaq; Jahanpanah (mid 14th century) built by Mohammadbin- Tughlaq; Ferozabad (1354 AD) built by Feroze Tughlaq; Dilli Sher Shah (Shergarh) (1534 AD) which was initiated by Humayun and extended by Sher Shah; Shahjahanabad or Old Delhi, mid 17th century built by Shahjahan, and finally Modern Delhi, built by the British in the 1920’s.

- Labyrinths: Selected Stories & Other Writings by Jorge Luis Borges, New York: New Directions Publishing, 1964, edited by Donald A. Yates & James E. Irby.

- For a fuller description of the Sri Yantra see Saundaryalahari, (trans.) VK Subramanian, Motilal Banarsidass, Delhi, 1993.

- Michel Fouault Of Other spaces in The visual culture Reader ed Nicholas Mirzoeff Routledge NY, 2002.

- Poems of Love and War, From the Eight Anthologies and Ten Long Poems of classical Tamil selected and translated by AK Ramanujam, OUP New Delhi, 1985.