Man has been presented again and again, in every epoch with a new purpose and conceived in a new image. Each time he rises like a phoenix from the ashes of the past, he preserves older traits of himself. “Ecce Homo” or “behold, the man” resonates through time equally as an indictment and a prophecy. But all prophecies lead to martyrdom, rather than redemption. All human beings are etched with the memories of their previous versions. From the ideal to the naturalistic to the disproportionate to the abstract, the visual form that man takes are numerous. Also, from the monstrous to the hedonistic, from the prophetic to the tormented, from the contemplative to the existential and from the revolutionary to the fragmented, alienated, dehumanised, dismembered man of the present, the passage has been enormously lengthy. In each version, man’s nature embodies the Hegelian belief that “the philosophy is an epoch captured in a thought.” Thus, each art movement too is an epoch captured in an image.

In a history inhabited by various versions of the man, we stand at the cusp of time anticipating a post-human cyborg of the future. Our present bodies are the bridge between the animal and the Nietzschean “superman”. Though we believe that we are at the pinnacle of civilisation, Konrad Lorenz has pointed out that we haven’t shed our primal instincts. Freud has prophesised that eventually we will be born anew as prosthetic gods armed with artificial auxiliary organs which make us magnificent. Each day we are presented with new possibilities such as cloning, manipulations of the human stem cells, genetic engineering, artificial selection, mind-altering psychotropic drugs, etc. Such possibilities lurk on the horizon making the future of mankind uncertain and ever more contingent on the decisions of today. We are indeed in a situation that most of us never imagined. Forty years ago mankind’s greatest threat was a nuclear catastrophe. Nonetheless, in the recent years we await a new cataclysm; something which has not been forecasted. What we have achieved, and what we are aspiring to become- especially as perfect bodies, happy souls, a more peaceful and cooperative society, etc., also posits risks which are unknown to us. We have become vulnerable not only because we attempt to become prosthetic gods with the aid of auxiliary organs and technology, but also because we seek immortality. In the pursuit of perfection we have exposed ourselves to the predicament of an undefined peril. The many literary and mythological precedents at our disposal show us the devastating consequences of such pursuits. Scaria’s sculpture Hesitant Attempt refers to such an example from Greek mythology, the tragedy of Icarus who in an attempt to give wings to his fantasies came ignobly crashing down to earth. The hesitant figure standing on the top of a hubris of unstable structures, delicately balanced upon a house, warns us against our mad rush into this new horizon of perfection.

Like Scaria’s Icarus we appear helpless, but we also lack the decisiveness to preserve the essence of the humanity, retreating to the jouissance offered by the virtual and the material. Our digitised avatars lurk in in the darkest of alleys of the World Wide Web; as tiny cursors we are doomed to navigate the neverending labyrinth of information highways. Mankind, or what we understand it to be, Michel Foucault remarked, is washed away like a figure drawn in the sand. Perhaps he was right, we are witnessing the “death of the man”. Our time is apocalyptic, we are awaiting our own extinction.

In such apocalyptic times, dystopian anxieties and catastrophic events fog our existence. Gigi Scaria stands atop this wasteland, like Caspar David Friedrich’s wanderer perched upon a rocky precipice, speculating an ominous new world. In an early work, Wanderer above the sea, Scaria or the wanderer surveys the burgeoning landscape of urban architecture sprawled in front of him. This image of the city has been our reality over the past decade and perhaps, is our only future. As Satyanand Mohan has noted, Scaria conjures up the city “as a living organism, as a site of potential chaos, and possessed of powers that elude control.” Nevertheless, I would also like to add that this wanderer standing frozen in time is witnessing the end times brought about by the environmental and existential destruction of humanity by its own technology rather than that which is predicted in theology.

In such apocalyptic times, dystopian anxieties and catastrophic events fog our existence. Gigi Scaria stands atop this wasteland, like Caspar David Friedrich’s wanderer perched upon a rocky precipice, speculating an ominous new world. In an early work, Wanderer above the sea, Scaria or the wanderer surveys the burgeoning landscape of urban architecture sprawled in front of him. This image of the city has been our reality over the past decade and perhaps, is our only future. As Satyanand Mohan has noted, Scaria conjures up the city “as a living organism, as a site of potential chaos, and possessed of powers that elude control.” Nevertheless, I would also like to add that this wanderer standing frozen in time is witnessing the end times brought about by the environmental and existential destruction of humanity by its own technology rather than that which is predicted in theology.

Scaria’s propositions are not restricted to mankind alone; he also offers a strong commentary on the role and function of art. Through the works produced for this show Scaria postulates that perhaps it may be impossible for art to escape ideology, however it may be able to how ideology functions. Scaria lays bare ideological operations and raises important questions about what art and philosophy have become, and what they were not able to. In his sculpture titled Thinker, reflects on the very predicament of philosophy and art, by recasting the iconic sculpture made by Auguste Rodin. Unlike Rodin’s monumental sculpture which was placed on a large plinth, Scaria’s Thinker is taken out of time and positioned inside a well gazing at its depths. Scaria’s relief panel, compared to the round work of Rodin, unsettles us at many levels. The entire structure gives an unstable feeling due to its two dimensionality and its ambiguous placement. Scaria’s brooding thinker contemplates in despair, alienated from this world.

The central concern of Scaria’s exhibition is mankind itself, its essence, the meaning of existence, man’s relations with society, the world, and finally destiny. The video work titled Disclaimer continues Scaria’s critique of capitalism and its enchanting narrative of development. We see the hands of magician moving the bowls, not swiftly but very slowly, unravelling a series of objects and finally revealing images of dead bodies of citizens murdered in the recent past. This video acts as a strong commentary on the nexus of capitalism and communalism which draws its inspiration from an imagined past and sells the dream of a better future. In the contemporary Global and Indian context, one cannot ignore the rise of right-wing populist regimes, religious fundamentalism and its close ties with capitalism. The right is not only destroying the idea of a welfare state and the various democratic institutions but it is also destroying every space of emancipation. On the one hand the problems of inequality and exclusion continue to thrive while they polarise the society using a conservative nationalist language of sovereignty, security, and purity. This ideology also seeks its legitimacy by presenting the narrative of development or progress in a distant future. This model of economic development deeply embedded in the political mythology of the right has no space for the marginalised. According to the right they are the “parasites” which need to be cleansed for the betterment of the collective future. Therefore, dreaming collective’s desires can only be fulfilled through encounter killings, displacements, genocides and other such violations of rights.

In the series of paintings titled Conviction, Scaria refers to an act of devotion mentioned in the Hindu mythology where the image of deity rests in the heart of the devotee. By tearing apart his chest, the devotee affirms his unconditional loyalty to the supreme power. In Scaria’s paintings, man repeats the same act symbolically, and in doing so pronounces his servitude to the right. This act, in Scaria’s works reveals the hollowness that resides at the heart of such ideologies. Through this series, Scaria meticulously reflects how the body is embedded in a nexus of power and is subject to various disciplinary technologies. Foucault has already shown us how the body is in a discursive condition, caught between power and knowledge. Ideology is inscribed in every individual body. Drawing inspiration from such philosophy, Scaria also shows us how subjectivity is formed by different modalities of power. He mocks the dominant masculine perceptions of the male body and exposes the ideological control on bodies.

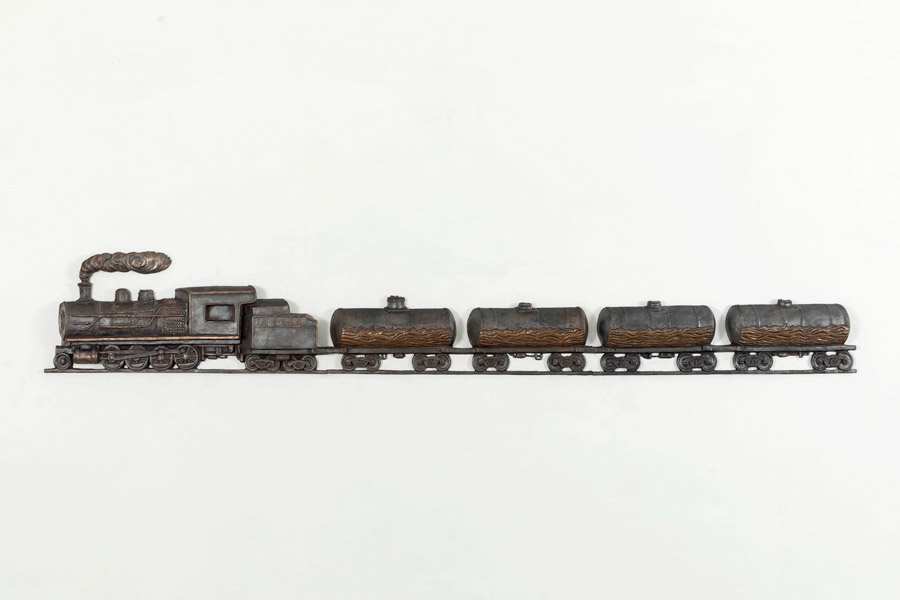

One can also connect Scaria’s work Train with the ideas of progress, history and revolution. Walter Benjamin disagreeing from Marx, according to whom revolutions are the locomotives of world history, argued that revolutions are like emergency brakes which has to be applied from time to time. He writes, revolutions are the act by which the human race travelling in the train applies the emergency brake. Nonetheless, neither of these revolutions have come to pass. The train of “progress” is moving ahead at a greater speed. Nevertheless, the train is racing towards crisis at an even greater speed, trampling millions across the world, in its wake.

There is a recurring image of man found in most of the origin myths across the world. The image of a man casted away to toil hard and die on earth awaiting a Promethean intervention and eventual redemption. The crude, fragile and naïve mankind is redeemed by the saviour or the messiah. The Prometheus or the Christ or the Prophets have resigned from their task of redemption. “God is dead”, pronounced Nietzsche years ago announcing a world where morality and ethics had to be rewritten in the wake of the domination of enlightenment values. The only similarity between eschatology and science at this time is that both share a vision of apocalypse. The secularised myth of the end of the world has become a technological possibility. Gigi’s exhibition embodies the Nietzschean maxim and spirit, to “philosophise with a hammer”. His works hit us hard exposing the pretention, complicity and self-deception ossified in our daily lives. The journey of man beginning from the Garden of Eden will eventually end in the Golgotha, and the resting place will not be in the clouds. The sanctuary is breached and humanity is reduced to a biogenetic structure, exposed to the possibilities of its extinction like never before. The video work Climb, shows us a man engaged in a futile attempt to climb and escape. The banality and futility of this act is repeated in different screens. An escape from this situation will only lead to a desolate desert of hopelessness. We are standing at the threshold of end days, beyond which there is an unknown abyss. In Scaria’s sculpture Fall, we already see the human being put at rest, who resigned to its fate. Death stares us directly from the sculpture, the man offering no resistance, raising questions about our future, our moral and physical fatigue, and the dangers of exhaustion in our pursuit of perfection. Is the twilight of the mankind over? It seems like the long winter of mankind is already here.

Important References

- Nietzsche, Friedrich Wilhelm. Ecce Homo Complete Works, Volume Seventeen, May 30, 2016.

- Foucault, Michel. Discipline And Punish: The Birth of the Prison. New York :Pantheon Books, 1977.

- Hegel, G. W. F. The Philosophy of Right. Indianopolis/Cambridge: Focus, 2002.

- Benjamin, Walter, One-Way Street and Other Writings, Harvard: Harvard University Press, 2016.

- Žižek, Slavoj and Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph von Schelling. The Abyss of Freedom. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press. 1997.